Let There Be Translations: Why India Must Embrace Its Multilingual Literary Wealth

A few years ago, I embarked on a rather tedious quest to find the English translation of Agnisakshi, a novel of the popular Malayalam writer Lalithambika Antharjanam. Needless to say, it was not as easy as popping into the neighbourhood bookstore, even though I lived in Delhi, the publishing hub of the country, at the time. That is when I realised the neglected state of translations of Indian writing. We do have institutions such as the Sahitya Akademi and the National Book Trust that have been resolutely pursuing translations of Indian literature to Indian languages as well as to English. However, many of these works tend to be perceived as “classics”, or high-brow literature intended for literary connoisseurs alone, and rarely make their way to bookstore displays or bestseller lists.

However, blessed winds of change seem to be sweeping across the publishing world today. Many of India’s big publishers have now awakened to the vast untapped potential that a country with 22 official languages and more than a hundred regional languages has to offer. Apart from boosting sales volumes and exposure for the writers, translations, while celebrating the multiplicity of our languages, can help deepen our literary experiences.

If translations between Indian languages in pre-independent India helped foster the idea of a ‘nation’—making writers such as Tagore a household name—it is quite possible that a shared linguistic ecology will help integrate an otherwise diverse bunch of people. Despite today’s modern modes of communication giving us easier access to news bytes from every corner of the country, it feels as though there is an increased ‘othering’ of cultures that are either not one’s own or not seen as one’s own. The kind of divisive politics and cultural crusades we see today thrive on promoting a myopic view of life on the basis of caste, religion, geographic boundaries, ethnicity, etc. And this is where translations of literature exploring the human condition can help. Literary translations can be the synapses through which cultural exchanges can be experienced, thereby fostering mutual understanding and acceptance of others.

Of course, any author will be delighted to see his or her work being translated into other languages. However, one big challenge that the industry faces is the scarcity of qualified translators. With little formal training available for aspiring translators in the country, it is no surprise that successful translators of books written in Indian languages are few and far between. Not to mention the fact that the lack of a structured model for payments and translation rights makes full-time literary translation a difficult profession to pursue. Introducing more mentoring programmes and training courses can help bring in the much needed resources to this field.

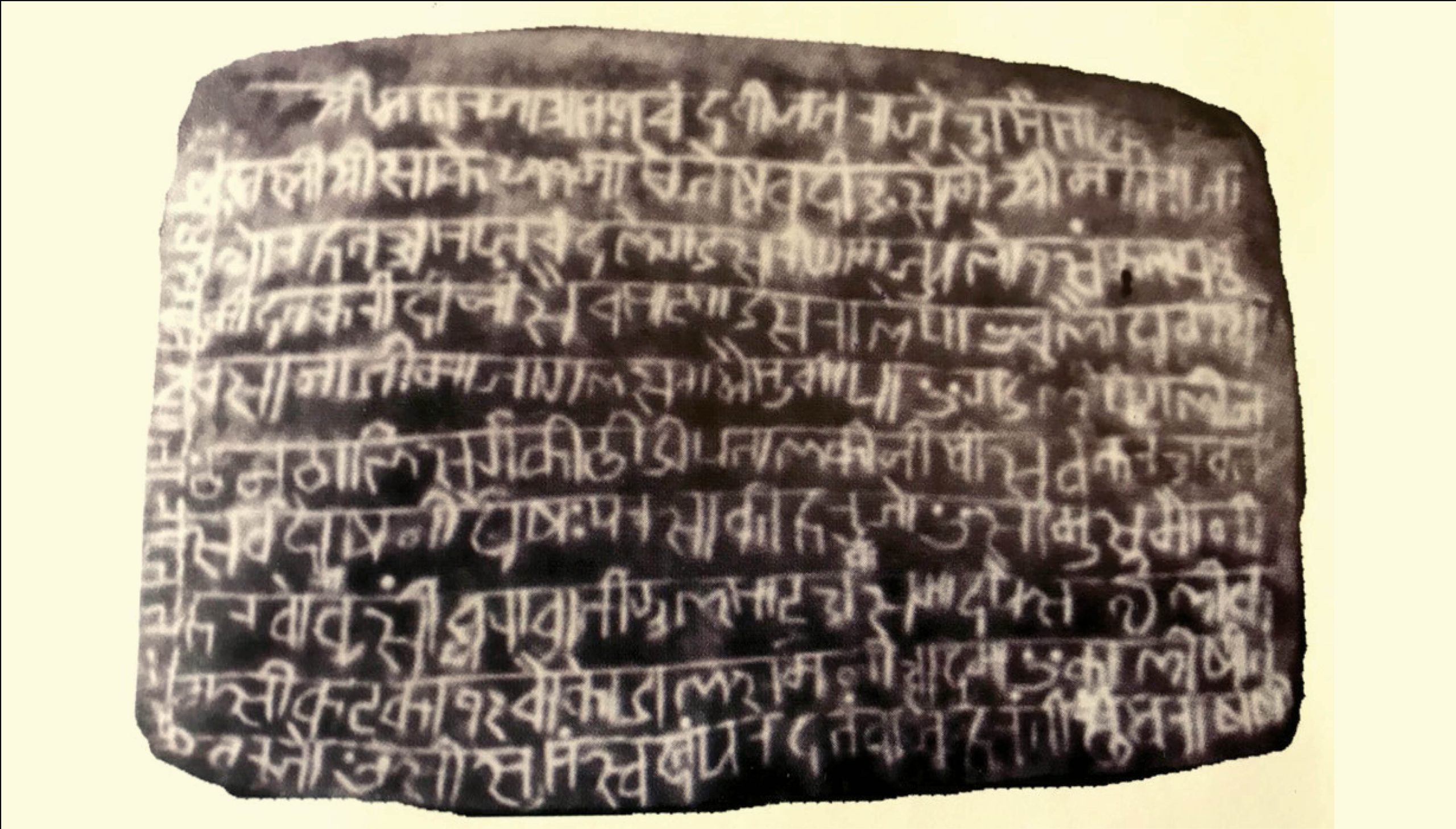

But it is not enough to have translations between just Indian languages and English. With its cornucopia of literary styles, themes and forms, India has the ability to offer the world a vibrant and incredibly rich collection of stories. However, very little is being done by the powers that be to make Indian literature available in world languages. We do have institutions such as the Indian Council for Cultural Relations (ICCR) attempting to boost cultural ties with other nations through literature, as seen by the festival organised by ICCR in collaboration with the Tehran embassy during the Prime Minister’s recent visit to Iran, when he released the Persian manuscript Kalila va Dimna—a translation of tales from the Panchatantra and the Jataka. Such events do help boost literary ties between nations, but they are not enough to take our contemporary writings to the world.

What we do need is an independent agency that can serve as the mother ship for all publishers, authors and translators. Such an agency, funded both privately and by the government, can work dedicatedly to facilitate translations of Indian writing into other Indian as well as foreign languages. The Indian Literature Abroad (ILA) project was such an initiative, launched in 2010 and backed by the Ministry of Culture. To oversee the project, a distinguished advisory committee of well-known figures from the fields of literature, translation and publishing was set up. ILA was to bring out Indian language writing in six languages—Arabic, Chinese, French, Russian, Spanish and English. However, it soon ran into bureaucratic troubles and its efforts seem to have come to a halt.

Sadly, funding for literary projects does not seem to rank highly on ministries’ agendas. We can take a leaf out of Turkey’s Ministry of Culture and Tourism, which has a Translation and Publication Grant Program (TEDA) dedicated to supporting and promoting Turkish literature worldwide, and has successfully done so in the past decade. Orhan Pamuk and Orhan Kemal are a couple of the biggest successes from this programme. According to this news report, Turkish literature has today travelled to 57 countries in 53 different languages. For Indian literature to make its mark in the international arena, a wilful participation by the government, publishers, writers, translators and literary fans will go a long way.

As for the domestic market, the recent entry of more players into the fray should give it the much needed impetus. As someone who is constantly seeking diverse stories, I look forward to the day my neighbourhood bookstore’s display will be peppered with beautifully translated books from all over the country.