Beyond the Coffee Table: Rethinking Illustrated Art Books

Why Illustrated Art Books Still Matter In A Digital-First World?

Illustrated books are often dismissed as “coffee table books.” How do you see The Met’s publications pushing against that label, balancing visual richness with intellectual depth?

I don’t find the “coffee table book” label to be dismissive or at odds with a desire to educate or convey big ideas. Making an object that people want to prominently display gives the book the potential to reach more readers. Beauty or brains is a false dichotomy. The Met’s publications are first and foremost built on Museum scholarship. Our books seek to fulfill the Museum’s mission to collect, study, conserve, and present significant works of art across time and cultures in order to connect all people to creativity, knowledge, ideas, and one another. In scholarly writing, there’s often a confusion between depth and complexity for complexity’s sake. In my view, our most successful publications are those that convey their ideas as simply and clearly as is possible given the subject matter.

When a book depends so heavily on images, how do editorial and design teams collaborate to make sure visuals don’t merely decorate the text but speak alongside it?

The leaders of our department (Mark Polizzotti, Publisher and Editor in Chief; Peter Antony, Associate Publisher for Production; and Michael Sittenfeld, Associate Publisher for Editorial) are in constant communication with each other and their respective teams. They establish the scope of each book at least two years before publication. This includes number of words, pages, and images. While also necessary for budgeting purposes, establishing this information early allows our teams to consider the look and feel well in advance. The Met has a deeply considered design review process that is particular to each book. Our production team expertly manages the design and meticulously color corrects the images. Their high standards ensure the illustrations offer their own information in support of and as an extension of the text.

Museum publications today reach far beyond scholars. How do you think illustrated books can make complex art histories and curatorial research more accessible to general readers without oversimplifying them?

It is important to define the audience from the start of a project. There’s no such thing as a “general” reader or a book that will completely satisfy both the scholar and the novice. The Met creates books for a variety of audiences. For example, our exhibition catalogues target high school to college-educated readers with some interest or background in art, while our How to Read series is aimed at early college or late high school students learning about a topic for the first time. Some of our collection catalogues are geared toward postgraduate readers. The goal of any book should be to reach the broadest readership of its intended audience. If a book has a target audience of just one hundred people, we want to reach as many of those one hundred as possible. A book on Cypriot glass, which sold through its digital print run of fewer than 200 copies, and Alexander McQueen: Savage Beauty, which has more than 418,000 copies in print, are both successful in hitting their target demographics. There is space for both types of projects, but it is important not to confuse one for the other.

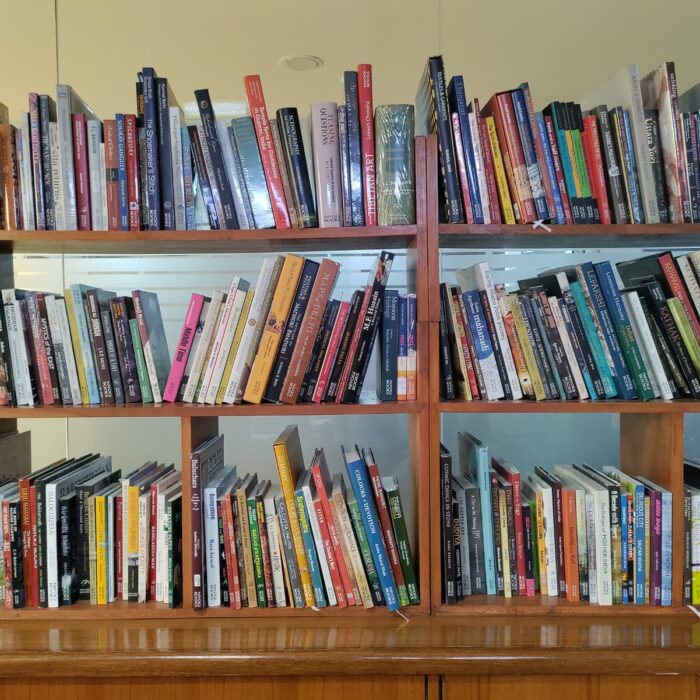

In an age of digital catalogues and online exhibitions, what role do printed illustrated books still play? Do you think their tactile, material quality changes the way readers engage with art?

One of the strengths of printed illustrated books is that they serve as works of art in their own right. Beautiful paper, exquisite printing, and luxurious materials can’t yet be replaced by the screen. I think a physical book invites readers to spend more focused, undistracted time with works of art, especially art books, which tend to be larger and less portable. That said, there is great value in digital publications for research and accessibility. The Met’s online publishing platform, MetPublications, hosts more than 1600 Met titles available to download for free. We link our digital downloads to the Museum’s Collection Online so readers can access the latest scholarship on each object.

Working with artworks often involves intricate rights and reproduction permissions. What are the unique challenges of managing these for museum books, especially when they aim to be both beautiful and educational?

The Met is fortunate to have an Imaging Department of staff who photograph works in the Museum collection and, on occasion, works owned by collectors or other institutions. This simplifies many aspects of image rights for us and allows us to offer beautifully produced images to other organizations, some available at no cost through our Open Access program.

However, The Met’s robust exhibition schedule includes domestic and international loans, so there are still many images to gather for our catalogues. This is expertly handled by a team led by our Senior Image Acquisitions Manager, Elizabeth De Mase. Elizabeth and her team ensure that we always have the best image for each publication, which requires detective work and diplomacy with both internal and external partners.

One unique challenge illustrated books face is the potential for licensing. The Met typically clears image rights for World English distribution. When we license translated editions, we ask our partners to clear images not under Met copyright for their territory and language. This requirement can complicate a rights sale when there are multiple images outside of the Museum’s copyright. A subset of our books contains only images owned by the Museum and we’ve had good success licensing this material.

Looking ahead, how do you imagine the illustrated art book evolving, whether in form, audience, or storytelling? Are museums rethinking what an “illustrated publication” can be in the 21st century?

Museum publishers need to consider their audiences more than ever and lean into the things that make illustrated books unique objects. Despite the recurring declarations that print is dead, Library Journal’s Generational Reading Survey found that both Gen Z and Millennial readers prefer physical books. The younger generations are also social readers, pulling recommendations from friends, family, and those they follow online. Aesthetics are more important than ever and that’s something illustrated books can do really well. Increasingly, publishers will need to build a physical and online community around their programs.

Gen Z is the most ethnically and culturally diverse generation to date. Art publishers need to tell a wider range of stories with more nuance. Several recent Met books have invited the perspectives of artists, poets, musicians, and cultural figures. I think texts representing multiple voices will become more common and expected.

Global reports show that the next generation of consumers expect ethical products that are also affordable. The Met is working toward this. All of our newly published books are Forest Stewardship Council certified, and we are offering books in varied price points and formats.

Readers are asking for books that build community, care for the environment, and tell authentic stories. At a time of AI slop, we want books to be more human.

Rachel High is Manager of Editorial Marketing and Rights in the Publications and Editorial Department at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. She oversees the MetPublications website, the Museum’s text licensing program in all languages, and the @MetPubs Instagram account. Rachel serves as project manager on certain exhibition and collection catalogues as well as the Museum’s co-publications. She has been a speaker at the National Museum Publishing Seminar and is an organizing member of the International Association of Museum Publishers.

Rachel High is Manager of Editorial Marketing and Rights in the Publications and Editorial Department at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. She oversees the MetPublications website, the Museum’s text licensing program in all languages, and the @MetPubs Instagram account. Rachel serves as project manager on certain exhibition and collection catalogues as well as the Museum’s co-publications. She has been a speaker at the National Museum Publishing Seminar and is an organizing member of the International Association of Museum Publishers.