Translations At A Crossroad: The Rising Power of Language In A Globalised World

Just a few days back I met a family of three; mother, father and a five-year-old girl. The father was Bengali and the mother non-Bengali. During the course of the evening the parents sat separated by some distance. The curious little child first asks her baba a question and he obliges her with an answer. I decided to follow her and see what she does next. As expected, she ran up to her mother and had a word with her. She went back to her father again with the outcome of her discussion with her mummy. The behavior cannot be considered to be unusual in any way. But, what interest me was how she effortlessly not only switched languages but also translated the content. Barrier of languages is now a thing of the past as translations have become a part and parcel of not just the mode of speech, but also movies, books and even music. Translation, thus, has become a very important enabler of communication.

In continuation to the previous article on translations by Archana Ramachandran, which spoke about the growing political and governmental keenness to promote the art of translations and the way ahead, there is dire need to also give credit to the other activities, which simultaneously, have being helping in the 360-degree reinforcement of translational activities.

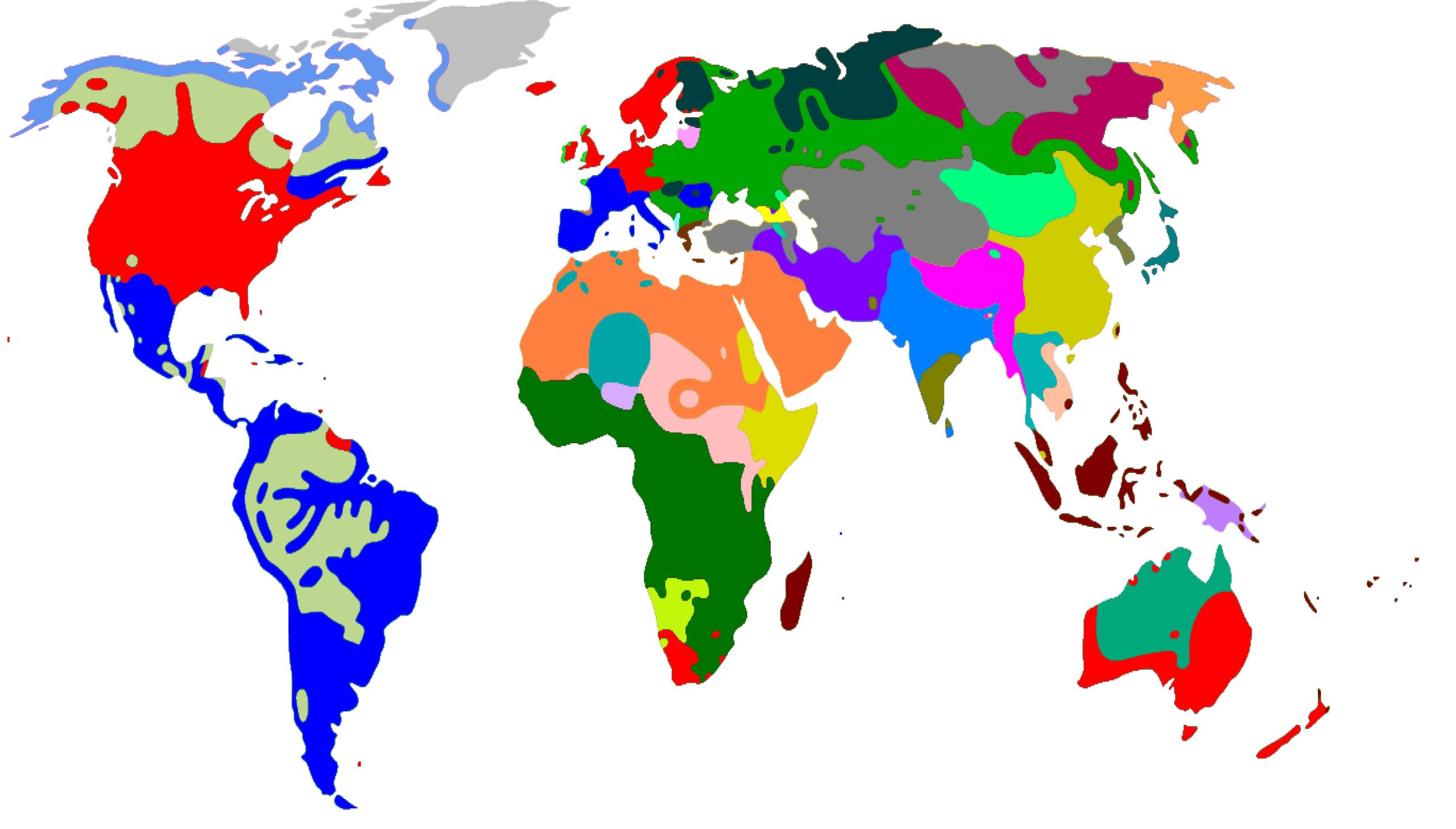

Translation can be seen as a cultural activity, which is gaining the academic appreciation and the literary credibility and significance over the years. This is only natural, given that the term globalization has now come way to becoming a reason for the interlink and interdependence between various economies, culture, and even ethnicity. Cross fertilization of cultures all across the world, as a fortunate outcome of globalization, made world literature appeal to human curiosity. Thus came the concept of world literature. Translations and multilingualism, seems to have made ‘world literature’ a much wider concept, than just another term in the vocabulary of the intellectuals.

At a point of time, translations seemed to be unidirectional and myopic in nature. But, now the asymmetry is being challenged and the voracious readers of the world seem to have got caught up in the maelstrom of literature. When Gayatri Spivak translated Mahashweta Devi and when Philip Gabriel translated Murakami, it brought forth a whole new readership for the authors, which otherwise would have been limited to Bangla and Japanese respectively. Were it not for the surge in translations, Márquez, Murakami, Tagore, Munro, Pamuk, Neruda and many more would have been out of our reach.

Today, translations, which used to make up a minuscule portion of the publishing portfolio, have come a long way to becoming a mainstay for many publishing houses all over the world. Even though, much remains to be done for translations and translators, we cannot deny that the biggest of fires start from the smallest of flames. And the direction of the wind is responsible for the direction of fire: annihilation or revitalization. For translations, the wind has started blowing as the governments of the world, along with publishing houses of all shapes and sizes, pursue translations directly as well as through bridge languages; the translated works are now gaining traction.

In all seriousness of purpose, translation studies, abroad as well as India, is an independent and evolving discipline. It doesn’t treat translations as just another subject but as a transfer of culture. Translation studies is an intermediary which embraces history, anthropology, social sciences, ethnography and many such discipline together to understand how a text is decoded from its original language and re-coded in target language. In India, it was only in the nineteenth century translation became a significant intellectual issue given the need for realization of multilingual and multiethnic nature to ‘imagining a nation’. The questions pertaining to the regional and linguistic identities became prominent during the process of linguistic reorganization of states. Each language needs a different approach of translation, as it isn’t limited to only linguistic and literary but cultural conveyance. Now that, it has already been understood that translation studies are required, the present situation is looking up, given the courses given in several universities including IGNOU, JNU, DU and Jadavpur Univerity in India. Similar small term courses, like the National Translation Mission (NTM) scheme under the Central Institute of Indian Languages (CIIL), to translate knowledge-texts into 22 languages in the 8th Schedule of the Constitution of India, in order to modernize indigenous languages and democratize knowledge. Thus, it is no doubt that the quality of the translations and the dexterity of their purveyors are scaling newer heights.

However, the economics of translations still remains unviable to pursue translation as a full-time vocation. They are highly passionate beings. With their day jobs they pay their bills but wield the pen by the night to fuel their passions. Translators still cannot dream of living off their earnings just yet. However, now translation prizes could be a game changer.

There are many awards given to authors, but very few to translators. The newly evolved Man Booker International Prize, which is awarded annually for a work of fiction, translated into English gives 50,000 GBP to be shared between the translator as well as the author. Even the shortlisted duo gets 1000 GBP. This has globally brought the translations from the circumference to the eye of the maelstrom. The 2016 prize declared two months back, brought South Korean author Han Kang’s ‘The Vegetarian’ on the wish list of many readers all across the globe. Thanks to Kang’s translator Deborah Smith, the book can be read all across the world and is not limited to the domestic boundary.

Back home, pre-eminent among prizes are the Hindu Prize for translation and the Crossword Book Award for the best ‘Book in Translation’ which give these magicians, Rs 5,00,000 and Rs 3,00,000, a small amount for their work, but the recognition they absolutely deserve. But, the prestigious Sahitya Akademi Translation Prize have been around for several decades and have painstakingly selected the best works from over 22 languages. The translation award by Muse India, even though lesser known, nonetheless, is of great prestige for young authors and their translators.

Another major local literary award in fiction, the DSC South Asia Literature Prize treats English translations with the same regard as it does for original works in English. The breakdown of the parity is music to the ears to many a translator, as this is what every stakeholder in translated works aspires for. The gap between the critically acclaimed and popular needs to be narrowed down, so that at least awareness can increase in the short run if not the sales, thus renewing the enthusiasm of many talented indigenous translators.

The new direction for translations, given the several aggressive initiatives taken by government bodies across the world, along with the awakening of the media and of readers is a sign that we need to keep moving forward. The fate of translations is in the hands of publishers, translators and other aficionados. Ghalib had written,

“Hathoon key lakiroon pay matt jaa ae Ghalib,

Naseeb unkay bhi hotay hain jinkaay haath nahi hotay … “

This aptly describes the current situation. When translated it reads thus:

“Don’t go by the lines on the palm of hand Ghalib,

Luck is bestowed even on those who don’t have hands…”